i feel like i’m on the precipice of madness

all of the time

there is only a narrow gap between me and no connection

or maybe it’s someplace else

i can’t see it

can hear it

it doesn’t make sense to me

she believes everyone is confused

as confused as she is

it’s been a year of this fragile passage

staring

haunting

sometimes calling

beckoning

but i have things to do

where you see the abyss

when you feel the gap

when you can map its edges

there is no boundary

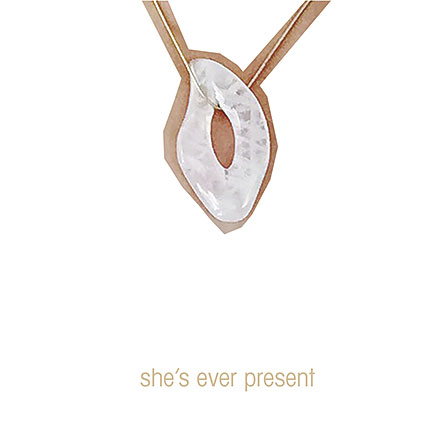

she’s ever present

Calling the great goddess of the ages

–from prehistoric to the furthest realms of the future–

gilded from the ages

radiant from lust

hot to touch

dripping sweat as I glide forward

this is my voice/my time/my demands/my temple

Bow down to me and listen to the murmurs

they are hymns you do not know how to hear

these are the women coming up from the below

we are rising

here we cum

as hot as fur

as sticky as sap

I smell of animal/feral/earth ridden

no time for my wings

no time to fluster

this is the beginning of our stride

turn these aisles, these pews, this all holy space into our cathedral

our strut will drop you to your knees

bend, fall, quiver, gather and conspire

there is no doubt that we have risen

SHE VOWS:

To make plastic art

Redefine plastic art

To make you love plastic art

To challenge and bewitch you with what you think is formal or plastic

To make you bow to her craft

Redefine craft

To weave

To weave your mind

To weave your mind into confusion

To drag you into the sacred without your consent

............................................................................................................................................

Download my complete thesis, SHE VOWS, here.

.......................

SHEVOWS (abridged)

Master of Visual Arts Thesis | Sarah Hewitt | April 2016

Gold Mylar streamers, blaze orange yarn, fuchsia flag tape, trimmings and fabric remnants: material cast-offs hang from the walls, waiting to be fashioned into forms. Images ripped from their sources are haphazardly hung throughout the space to constantly remind me of my focus, influences and kindred spirits. Michael Taussig’s Mimesis and Alterity, a portrait of Alina Szapocznikov, Aby Warburg’s writings about the Pueblo Indians and much more travel with me as my studio changes locations. A variety of artists and subjects grabs my attention. Wangechi Mutu, Paul Thek, criticism by Ann Cvetkovich, Robert Farris Thompson’s Flash of the Spirit, and Third-Wave Feminist rhetoric all influence my thoughts, my work and movements.

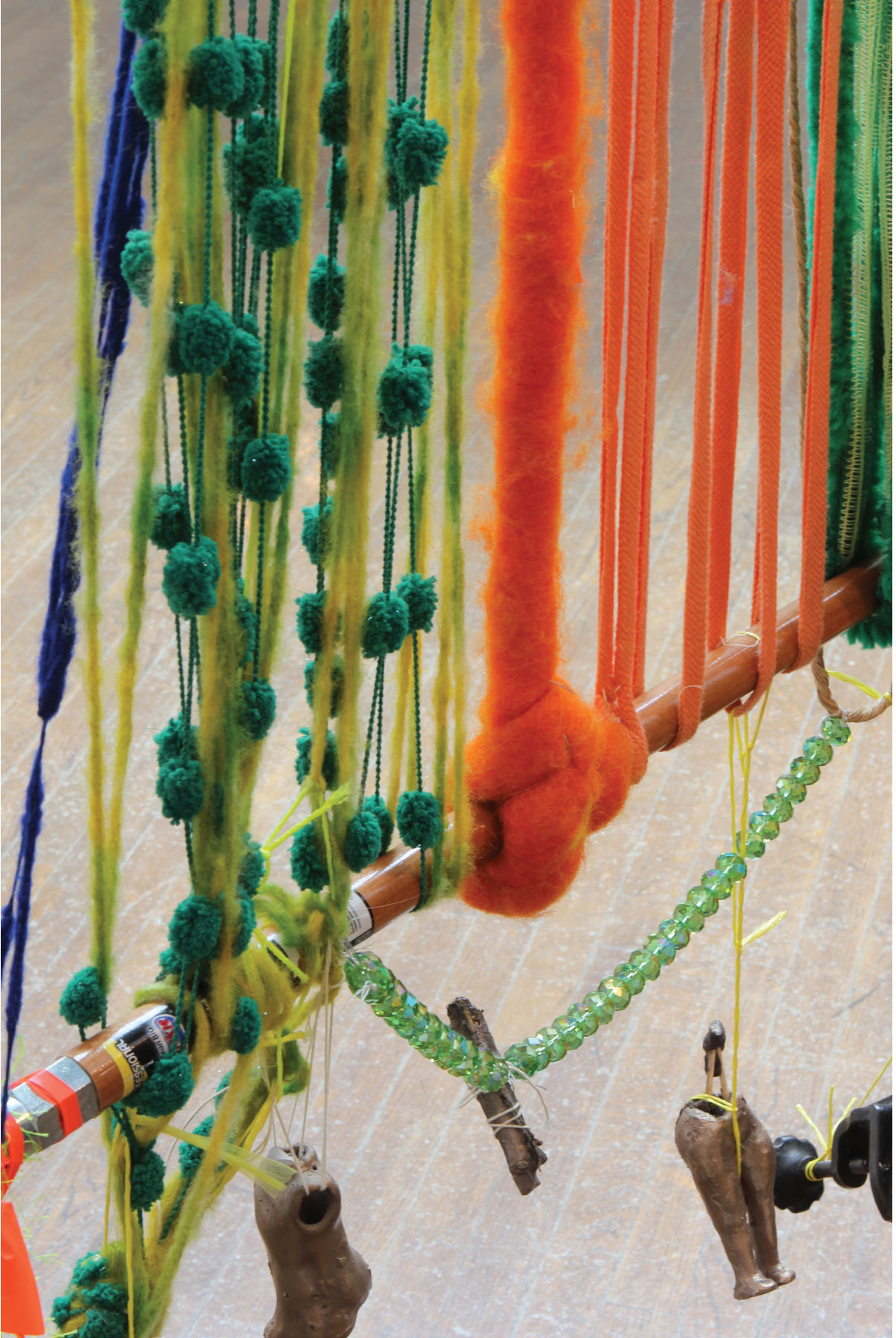

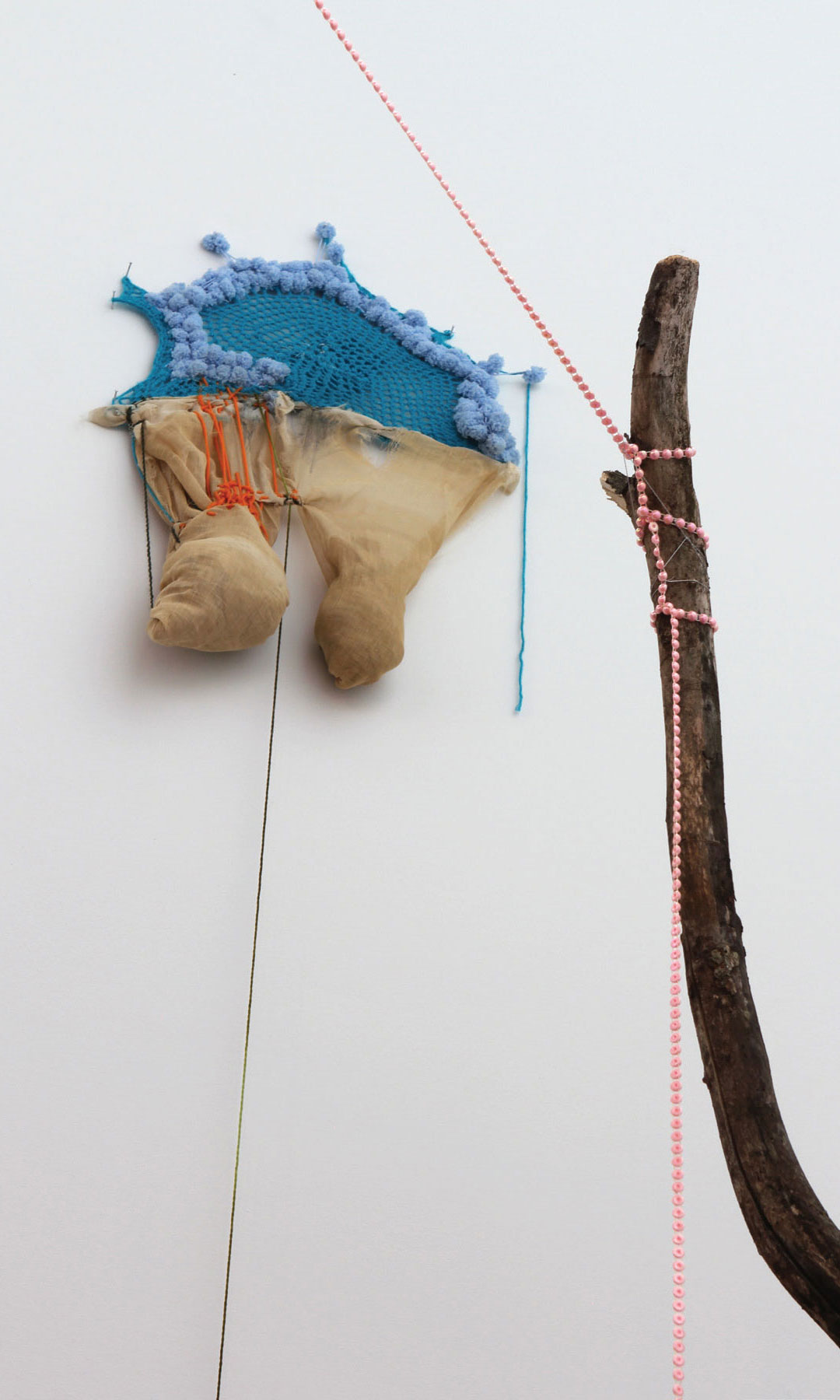

I wander about the studio weaving, crocheting, and stitching traditional and non-traditional textile materials. I carve and mold foam, plaster and clay, along with constructed skeletal structures made of pipe and wood remnants, into sculptural forms that inhabit their fiber environments. There is a riot of color in each construction. I am pushing and pulling each of the materials and techniques to clash to go even further—to dazzle and confound the viewer.

While under most circumstances I am unable to speak of my desire to beguile, confuse and deceive, dominate and supplicate, often with aggression and sexuality, it is in the forefront of my mind. My hands do not resist these contradictions but thoroughly embrace them, relish in them. When my hands are working, the truth of my thoughts sneaks around my reluctance and begs the materials to be bold, to hold court, to challenge and suggest.

.................................

I work in lists: lists of words, materials, readings, quotes, with flashes of commentary. This year I began to work on a manifesto, SHE VOWS, as an alternative persona—a bold and brash dominating feminist statement for my work and my direction. SHE VOWS is the box that I stand on and speak loudly about my concerns, how I truthfully work and where I hope for the work to go and take me.

There are many ways to look at my practice and maybe the work falls into too many categories and genres. It is messy and complicated. It is not linear or decisive, it is just like me–no map. But there are core truths to this body of work. I will start with a list of words and how I perceive they relate to my studio practice, followed by my criteria for each artwork and how my work will continue to develop.

.................................

Surrealism:

Relating to my work in the interest in the subconscious, play, mysticism, moving fearlessly into the unknown.

Surrealist heroines: Dorthea Tanning, Annette Messager, and Louise Bourgeois.

Transubstantiation:

Understood as the belief and dedication to empower objects with prayers, magic, and power. This is at the core of my practice. Every time I step into the studio I am entering a temple, a place of prayer and conjuring. Every work I create I imbue with prayers, songs, and blessings.

Joseph Beuys believed that all men are artists. Ishmael Reed’s “Neo-HooDoo Manifesto” proclaims that every man is an artist and every artist a priest.” Every life is an act of individual creation and in that I agree that every wo/man is an artist.

Every work of art is a prayer in one manner or another. There is dedication, thought, meditation and action involved in any creation. Amadou Hampâté Bâ’s essay “African Art: Where the Hand Has Ears” clearly and respectfully discusses how traditional African arts have been crafted in tradition and reverence, and in unity with daily life. There is no separation of life from art; sacred or profane, the artist is a “medium of transmission.”

The crafts of the iron-worker, carpenter, leather-worker or weaver were therefore not considered to be merely utilitarian, domestic, economic, aesthetic or recreational occupations. They were functions with religious significance and played a specific role in the community.

In 2010 I started weaving and constructing bundles of burlap that hung from points on the wall. They could be gathered and attached, belted and carried as burdens. They were monochromatic, roughly the size of backpacks, reminiscent of organs and tumors. I traveled around the country attending residencies, weaving and stitching these vessels knowing that they had something special about them. They were not pretty, but they were bewitching. I had begun to construct my own relics and spirituality.

Craft/Art:

The separation, or false separation, of craft and art has been a continuous conversation around my career. My work does not clearly fit into craft–even though I tried to hide in the areas of craft and craft schools—but crosses over defiantly into art. The work is intensely rigorous in its making, statement and visual presence. I use craft and the traditions and skills of craft as the backbone of my art practice.

I follow the craft tradition in dedication of time, skill, repetition and apprenticeship to the structure and principles of making. Itis embedded in my body and in the work. The skills that I have gathered to create these works have come over many years, from teachers from around the world. I deeply respect the tradition of making and how traditions lead to contemporary developments that will eventually evolve into new traditions. Craft is about the body, community, learning and commitment. My body knows the movements better than my mind and my hand imbues each form with my dedication and ideas.

My heroines of craft theory and discussion are Elissa Auther and Lucy Lippard. Both theorists understand the political and feminist views that some artists choose to express by using craft methods.

My heroes of crossing and teasing the art/craft divide are the artists Jeffrey Gibson and Tommy Lanigan-Schmidt.

Feminism:

I am a Third-Wave Feminist. Feminism stands for equal rights, justice and respect for all—especially women.

At first I was attracted to working with textile techniques as a Feminist political statement. Knitting offered me a connection to my grandmother; needlepoint with my mother; and weaving with my adopted dad. Familial connections supported the practice for me but I also relished the subversiveness of using woman’s work to create abject objects.

Today we are resurrecting our mother’s, aunts’ and grandmothers’ activities–not only in the well-publicized areas of quilts and textiles, but also in the more random and freer area of transformational rehabilitation.”

I no longer use the craft of textile techniques as a political weapon, as a signifier of my femaleness, my Feminist morals. At first, I happily grabbed on to that theme–just before the “Stitch’n Bitch” nation was forming. I loved the notion of taking up knitting needles, working in a craft my grandmother idled her time in. I created complicated, sutured, stitched and woven forms as stand-ins, decoys, fetishes that my grandmother would never have dared to lay eyes upon. I happily took to woman’s work to address the treatment I received from men’s hands and their authority over my life.

No longer do I work in that way but treasure the tradition, skill and knowledge of handworking with textiles. I want to exalt the stitch, the bindings, the colors and the chaos of threads. I want to make order of the infinite combinations and not bind my emotions and terrors up into the forms. Finally, in the past four years, I have moved beyond my need to release my memories in forms. I am working with the divine and sublime. I am here to transport the viewer to a new space—not ever to wrench them back to my experience of trauma.

Feminist heroines: Lucy Lippard, Judy Chicago, Miriam Schapiro, Mira Schor, Louise Bourgeois

Gender:

My works explore the gender spectrum and signifiers of gender. Each construction identifies itself with a specific gender or gender spectrum.

My heroines: Maggie Nelson, Judith Butler, Camille Paglia

Sexuality:

I explore sexuality by means of of humor and wit. The sculptures sometimes beckons to be handled or mounted. They may tease and entice or are used as declarations of sexual needs or sexual wounds.

Decoys and Fetishes:

I toy with the making of myself in weaving and constructions. Sometimes I want to offer the audience a different me for them to direct their attention toward. It is the trickster in me. Must I be present or could a stand-in be more effective? Which version of me will work best for the viewer? A humanoid or a beast version? Male or female? Maybe a vividly colored construction will entice you more than a monochromatic earthly concoction. A life-size voodoo doll is effective in gaining attention but makes the viewer uncomfortable. Now I include small, handheld fetishes along with my woven and constructed fiber environments. Do not let the size fool you–the tiny pieces are the center of the constructions and often direct the installations. There is voodoo in each work and often the small fetishes are the most potent.

Ritual/Constructed Spirituality:

My work is supernatural. It is a fusion of the future and the archaic. The content is universal and timeless. The materials are contemporary. My studio functions as a cave and my weavings are my cave drawings.

We know that the earliest art works originated in the service of ritual—first the magical, then the religious kind. It is significant that the existence of the work of art with reference to its aura is never entirely separated from its ritual function. In other words, the unique value of the ‘authentic’ work of art has its basis in ritual.

When I learned of the exhibition NeoHooDoo: Art for a Forgotten Faith, I felt that I had found my family. Here were contemporary artists gathered together in one venue, one catalogue, and the work was free to be interpreted as spiritual. Weekly I am told to not talk about the spiritual and ritual aspects of my work. But without this discussion the works may be read only in a formalist manner. I continue to work very hard in my choices of color and installation in order for the pieces to be read as possible prayers, rituals and a festival of the spirit. When a critic enters my studio and mentions Mardi Gras or Carnival, Sun Ra, a parallel universe atmosphere, then I know that the work is translating its position to the viewer.

My heroines and heroes: Vanessa German, Alison Saar, Janine Antoni, Terry Adkins, Jimmie Durham, Sanford Biggers

Textile:

Craft is sometimes cast as the trivialized, amateur “other” within the discourse of artistic labor–a mere leisure pursuit–or, conversely, seen as utilitarian or applied design. Yet many movements within modernism have also embraced handiwork and decoration (the Arts and Crafts movement and the Russian constructivists, to name just two). In the early 1970’s the feminist art movement embraced the procedures of “personal projects” of craft as a way to revalue women’s labor. While shunned by many modernist critics for its taint of amateur decoration, craft became a way for feminist artists to critique the denigration of domestic, female work within the art institution.

Learning how to knit from knitters in Maine, in a craft environment, offered me the chance to sculpt without formally knowing anything about sculpture and the principles of the discipline. I was making non-wearable figurative objects, things about the body but not for the body. We sat as a group, chatting and giggling as we worked many hours. It was casual and not pretentious. Nobody said look at my art. A community would form as the workshops advanced. Community always forms when people gather to stitch and learn new textile techniques. The community, openness, skill-sharing and supportive nature of textile work keep me identifying as a weaver.

As it stands, women–and especially women–can make hobby art in a relaxed manner, isolated from the “real” world of commerce and the pressure of professional aestheticism. During the actual creative process, there is an advantage, but when the creative ego’s attendant need for an audience emerges, the next stop is not the gallery but to become a “cottage industry.” The gift shoppe, the county or crafts fair and outdoor art show circuit is open to women where the high art world is not, or was not until it was pried open to some extent by the feminist art movement.

I happily teach and discuss methods and materials with anyone. Students come into my studio and see the stash of materials and study how I have transformed them. Transformation is the root of all textile traditions. How can you transform one material into something that elevates and celebrates the material and the structure? It is the starting point and it does not ask for high concept or lofty results. Just start with the material, the structure, and go from there.

The crafts, understood as conventions of treating material, introduce another factor: traditions of operation which embody set laws. This may be helpful in one direction, as a frame for work. But these rules may also evoke a challenge. They are revokable, for they are set by man. They may provoke us to test ourselves against them. But always they provide a discipline which balances the hubris of creative ecstasy.

The material is the dictator, and traditions of crafts, tools and good taste have created parameters for weavers to work in. I have decided in my work to expand those guidelines and create new tools that allow for me to open up the conversation into new areas, new forms—literally. My threads are not bound by their warp and weft. The warp may extend suddenly way up into the sky and hang without a binding, only to be held by the tension of a nail. My wefts almost never cover the warp–they get lost, lazy and wander about. Letting the threads have more control over their mapping has resulted in a freer expression of weaving. I am really drawing with the threads, without a bounding or cropping box. The drawing is now on the wall and the threads are now the gesture marks.

I am attacking space and planes with my threads. They are breaking the bounds of a rectangle and the loom and moving off on their own tangents. They are released into new forms, new maps and portals. The threads attack—it is an action. The threads are not decorative moments alone; they are the skin of the beast expressing its nature. They are rough and smooth, dull and shiny, hard and soft. There is a clash of colors and textures.

Hybrid:

There is a duality that runs throughout my work. It arises in the feminine and masculine—forms, material associations, sexuality and power. Nothing is pure art or craft. Everything is play and serious spirituality.

In the tradition of the Apache sweat lodge in New Mexico that I am a member of, I hold the tenets of two-spirit, both the masculine and feminine, within my thoughts. It’s not androgyny–it’s a third space, a new place of both and neither one nor other. But I do not limit my work to only the two-spirit sexuality. I want to converse with each side of the spectrum—the hard and the soft; the future and the archaic; the technology and handwork. I am not there yet—not to the point of fully embracing the duality of all tenets of the work—but I have begun to map out how my pieces may instill and embrace these challenges.

Trickster:

In African art the powerful object may not be the largest in the room. It may not be shiny—the most visually stimulating object might be the decoy to distract you from what truly holds the maker’s energy.

Works of art and architecture may invoke secrecy in one of three ways: by attracting attention to secret realms; by distracting viewers away from restricted places such as shrines, for example through public masquerades; or by containing or enclosing secret things.

These three principles inform my practice from conception to making to final installationin the gallery setting. What combination of objects will form the correct balance to entice but not overwhelm? How can my work engage but not create a overwhelming situation for the viewer? I orchestrate the energies, forms, colors, and space between the objects, environment and the viewer’s perspective. I have learned what kind of situation an imbalanced installation can create. I include objects within most installations as placeholders to allow the composition and energy some resting points.

I did not set out to be a trickster, a clown or a troublemaker. I take responsibility for the situations my work creates. I continue to study how to position the work and what works are private or public. Often I consider whetherthe work, my kind of work, should be exhibited and if so, in what kind of venue. A gallery may not be the appropriate situation for the constructions, but it is the locale and opportunity that I am most often offered.

Martha Wilson asked during a studio visit how I want the work to be effective. My response was that I am not sure if I have the work located in the correct space. If I lived in another era or region the works would be more appropriate for a temple setting or hidden in the landscape. But at this point I have not chosen to hide all of the works or invest them into the landscape. I burn some works, some are offered to animals in the landscape as shelters. These are my cave drawings but I do not live in a cave.

Material, Color, Embracing Bad Taste, Bold and Brash…

What I am trying to get across is that material is a means of communication.

I have chosen to set about making these works using a traditional craft, weaving, in a fine art manner of drawing, painting and sculpture. I have decided to use a woman’s traditional craft to make work that is not solely feminine—actually, it is much more beastly. These are the pelts of the creatures, the skins—the embodiments of a supernatural form. This is not an act of violence slaying but a manner in which I am introducing my viewers to my world without overwhelming them so they become fearful of the fully realized sculptural form. I am working with harmony—creating harmony within a chaos of colorful threads—but I am also hoping to push the harmony to the edges, towards the areas of less beauty and more bewilderment. How can I make something tantalizing, a spectacle, but also move to the bare edges of unseemly? I want to screw the eternal order—push, attack and expand the edges of what you call the eternal order and harmony. I need to go much further with the materials, the colors, the kitsch qualities, and the pop nature of the color palette and the baseness of the materials. I want to interject the chaos, the insanity, and the frailty of what is life right now into the soothing rhythms. I thoroughly want to mix the sacred with the profane. Let’s think of the sacred as harmony and the profane as syncopation. It would please me to create works that mimic the manner jazz riffs could displace sacred hymns. What is the spot that creates, and what would it be called?

Let the weaving be the sacred; the tradition, the rhythm, the standard, the craft and know-how passed from generation to generation. Let it be the cloth that covers, protects, seduces and honors. Let it be the value, the commodity it has always been. It is fashion, it is couture and it is handmade. But then let how it functions, how it installs within a space, how it fractures–be the profane. In how many ways could weaving be profane? Thus far I have broken the structure of the loom. I have not finished the stitches; I have not bound the materials so that they may hold their structure. I have rejected the more sophisticated, expensive and luscious materials I once used. I have sent the concept of using the best materials you can afford to make the most sophisticated product down the river. Instead I have turned to the cast-off materials I find at job lots. They are too loud, too ridiculous, and too tacky for the home hobbyists to take home and be made into their domestic and wearable fashions. These are the materials I have embraced and take time to search out. I combine them with hardware store finds of rope, twine and flag tape. The more neon the better…the stretchier the better. How far can I take this construction site material so that it will harmonize with the cheapest, trashiest yarns I can find? How can I make hundreds and hundreds of intersections and textile connections come together and sing? But the tune is not a hymn–hopefully someday it will reach a fever pitch and authenticity, something like Nina Simone‘s deep, dark, gravelly soulful voice as she calls to a man that she knows she has power over. Let the work be deep, dark, dirty and gritty. It must come from a place of authenticity. I am not looking to create a spectacle for fun or frivolity. This is serious business for me. This is crafting a new fabric in a new manner that is complicated–as complicated and fragile as our contemporary moments.

The stitches are loose and unbound. They stand with tension leaning on nails. Really, they are barely tethered. Soon the weavings are going to walk off the wall and into the gallery.

.........................

My Criteria

Within each work I complete the following three criteria must be acknowledged. The work may not fully succeed in fulfilling these points but I must be cognizant of them in the process of creating.

1. An intense point of tension must exist within each work so that I am constantly pushing myself in the making. I may choose materials that I stumble using or a scale that will push the limits of my physical strength and spread. Over the last three years I have learned that with each new work that I must challenge myself, to force myself to be uncomfortable with the process and content so that the work may continue to grow and develop. Often I am gathering materials I dislike at first handling; or incorporate something hard and unyielding in with a malleable material; force for the work to pull and push aspects of both male and female stereotypical qualities.

2. It is important for each of my works to refer to both the ancient and futuristic with an emphasis on the feminine in all its complexities. The concept, content, materials and presentation of the sculptures and drawings must honor both old traditions of ceremonial art as well as converse with contemporary times and our future.

3. The work must dance, entice, welcome and bewitch. The ideals embedded in the forms may be serious and heavy but I want to tempt the viewer to approach. The soft nature of the compositions, the color and material palette and associations they may have with the techniques to create the pieces calls the viewer towards them. We associate comfort, protection and nurturing with a work of fiber. I am pushing my constructions to engage as tapestries but also as oversized abstracted creatures. There is a fantastical aesthetic to the surface but they are rooted in an earthly ritualistic practice.

.........................

SHE VOWS:

To make plastic art

Redefine plastic art

To make you love plastic art

To challenge and bewitch you with what you think is formal or plastic

To make you bow to her craft

Redefine craft

To weave

To weave your mind

To weave your mind into confusion

To drag you into the sacred without your consent